The issue of large denomination gold coins was of particular importance for the sovereigns of Russia. From the 15th to the 17th centuries. these coins more often became rewards than means of payment. Or they were still used for payments, but only for international ones. Only since the 18th century. There is a need for such money in the country’s domestic market.

A coin made of “royal metal” emphasized the strength and independence of royal power, the sustainability of economic growth and encouraged foreign merchants to cooperate.

Russian gold coins: the beginning

“Chervonets” have long been the name for foreign and Russian large denomination coins containing high-grade gold.

Stable production of such copies in Russia began under Emperor Ivan III (second half of the 15th century). At the same time, the first gold coin of Russian coinage - the “zlatnik” of the Kyiv prince Vladimir - was issued five centuries earlier.

Its official name is unknown. The minting of zlatnik was important from a political point of view: during this period, Kyiv asserted its importance and established new relations with neighboring states. Under Prince Vladimir, the country did not have its own gold; instead of Russian coins, they paid with Byzantine or Arab ones.

The solidus of the Byzantine emperor, a rival whom the Kiev prince looked up to, was taken as a model for coinage. Both coins are similar in weight, gold purity and images on the obverse and reverse.

11 known examples of this issue were found in treasures discovered in the 19th century. Ten of them are in museum collections; it is unknown who owns the eleventh. Modern collectors can purchase a zlatnik in the form of a commemorative gold copy, issued in honor of the millennium of ancient Russian coinage (denomination 100 rubles, edition 1988).

Proof of status

Issues of small circulations of gold coins under Ivan III are explained by almost the same reasons as under Prince Vladimir. The Emperor unites the Russian lands, destroys the Tatar-Mongol yoke, and streamlines the laws. The Byzantine double-headed eagle had already become Moscow's; the Grand Duke had a different goal during this period: to prove the equality of Russia and its European neighbors.

During this period, English and Hungarian coins (“shipman” and “Ugric” gold) were used as models for minting. In addition to these foreign gold coins, Venetian and Dutch ducats circulated in Muscovite Rus'. The word “Ugric” was used to describe both Russian and foreign coins: this definition indicated the purity of the metal. The state still had not established industrial gold mining, so new Russian editions were minted from melted down foreign ones.

It is possible that Moscow gold was sometimes used to pay, for example, specialists invited from abroad. However, they were usually intended for rewards and gifts. A hole or ear was made on such a granted coin to be worn around the neck or hung on an icon. You can now see these gold ones in the museum.

Until the end of the 17th century, the rulers of Russia, following Ivan III, minted gold coins with their portrait and a double-headed eagle.

Origin of the name "chervonets"

The word “chervonets” was formed from the phrase “chervonets gold”: an alloy of copper and gold was used for minting. The result of combining metals corresponded to samples from 916 to 986. Even a small amount of copper in the alloy gives a reddish tint, so the color of such gold was designated by the word “red” (after the method of extracting red dye from the cochineal mealybug).

The official name “chervonets” during Soviet times was used for a new monetary unit, equal in gold content to a ten-ruble coin with a portrait of Nicholas II. Therefore, in recent decades, this word has often been used to refer to coins and banknotes in denominations of 10 rubles or anything in the amount of ten.

On chervonets issued before the 18th century, the denomination was not indicated: when calculated, they corresponded to silver rubles (from 1 ruble 20 kopecks to 3 rubles 50 kopecks in different periods).

History of Nikolaev Chervonets

The Tsar's Chervonets is a unique coin. Its minting has been carried out since the ascension of the last emperor to the throne. This happened in 1894, when the image of Nicholas II appeared on the reverse of the coin.

Golden chervonets of Nicholas II

The need for cash and the production of coins has always existed, for this reason Sergei Witte proposed to start minting banknotes. They were made from a special alloy of gold and copper. At the same time, the standard of the noble metal was high (900).

Minting continued in Paris and other European countries. It took place during the reign of the last emperor. Even after his death, the coins were successfully used by the Bolsheviks.

It was believed that the “new government” had taken the initiative and, in order to avoid the final collapse of the economy, continued the production of obsolete banknotes.

Numismatists around the world consider gold chervonets a mystery, since coins that are no more than 50 years old often appear at markets and auctions.

But this coin should not be considered rare; To support the country's economy, a lot of money was minted. It is believed that the minting of chervonets was ordered in various countries; even Japan produced banknotes at the request of the Russian Empire.

Money was made in large quantities until 1911, after which minting stopped. But these are official data. If you believe the sources, then in 1911 not many chervonets were produced, only 50 thousand pieces.

However, some numismatists suggest that the minting of coins continues to this day. This statement is controversial, but it largely helps explain the appearance at auctions of coins whose age does not exceed 10 years, according to experts.

Bloody events that affected the royal family, a change of power and the formation of a new state - all this attracts additional attention to the chervonets and makes the coins even more valuable. But we are talking about genuine signs, not fakes.

Chervontsi of the 17th century

After the Time of Troubles, the Romanov dynasty came to power in 1613. Before the monetary reform of Peter I, rulers minted award coins of a whole chervonets, part of it, or several chervonets.

From 1613 to 1682, both sides of such specimens were decorated with double-headed eagles; under Princess Sophia, there were portraits of Tsars John, Peter and their sister-regent. The traditional name “Ugric” was assigned to these coins (this is how they are called in modern numismatics).

The year of minting began to be indicated under Peter I (first in letters of the alphabet, then in Arabic numerals).

The connection of historical times is clearly visible on the double “Ugric” of Alexei Mikhailovich: the images on its sides in general repeat the golden prince Vladimir or the Byzantine solidus. Perhaps the appearance of such a chervonets is connected with the tsar’s plans to become the sole trustee of the universal Orthodox Church. One of two known copies of the coin is kept in the Hermitage.

Chervontsi of Peter I

The transformations of Peter the Great required the renewal of a dilapidated economic system, the crisis of which in the middle of the 17th century had already led to several popular unrest.

In 1701, coins of one and two chervonets were issued, modeled after the Dutch ducats. Unlike previous issues, Peter I's chervonets were intended not only for the purchase of goods abroad, but also for payments within the country. Gold sand for minting was purchased in China. At the same time, active development of precious metal deposits in Russia begins.

The chervonets of 1701 was made from 969 standard metal. It contained 3.36 g of gold and weighed 3.47 g (double chervonets - 6.94 g). It was distinguished from the ducat by Russian inscriptions (however, on the copy of 1716, intended for the Tsar’s trip to Europe, inscriptions were minted in Latin).

Chervonets, issued from 1701 to 1718, were distinguished by many small details, however, the main images were repeated: on the obverse - a portrait of the sovereign with a laurel wreath on his head (a symbol of triumph, the immortality of power), on the reverse - a double-headed eagle. The cost of these coins, which did not have a specified denomination, was determined by gold prices and did not exceed 2 rubles. 30 kopecks silver

Chervonets with a portrait of Peter I were in circulation before the reform of Anna Ioannovna.

Chervonets 1706

This coin is interesting because the year of minting on its reverse is indicated in letters of the Old Russian alphabet. The exact number of surviving copies has not been established.

Two-ruble chervonets

The need to replenish the treasury led to changes in the rules for minting chervonets. From 1718 to 1728, coins with the indicated denomination of 2 rubles were issued in Russia. For their production, gold of a lower standard was used than in chervonets of previous years (781 samples). It was obtained from melted down foreign coins. This gold coin received the name “Andreevsky” because of the design depicting the Apostle Andrew on the reverse instead of a coat of arms. It weighed 4.1 g - more than a chervonets without a denomination.

Two-ruble chervonets with a portrait of the ruling person were minted until the reign of Peter II, when they were recognized as unprofitable and inconvenient. Mints have again begun producing gold coins without a specified denomination.

Due to the peculiarities of minting, two-ruble chervonets of the same edition often differ from each other.

“Andreevskie Novodelnye” and more

It is interesting that the minting of two-ruble chervonets or coins with portraits of late rulers did not stop completely - a modern collector can get into the hands of even a copy from 1890. The remakes were made according to private orders; they participated in exhibitions organized by the government. Such releases were prohibited by decree of Alexander III.

An examination conducted by a specialist will help to distinguish a real chervonets, for example, 1718-1728, from its later counterparts.

Chervonets in the Soviet era

In the RSFSR, chervonets banknotes were issued, equal in terms of the gold backing to the tsar's ten-ruble coin (from the time of Nicholas II).

There were also coins of the same denomination. The 1 Soviet chervonets coins depicted a peasant sower (obverse) and the coat of arms of the RSFSR (obverse). These gold coins were exactly the same size and weight as the royal chervonets.

This coin was issued in 1923 and 1925. In everyday life they called her “the sower.” Difference between 1923 and 1925 coins - coat of arms. Earlier samples depicted the coat of arms of the RSFSR, and later ones depicted the coat of arms of the USSR. Moreover, the 1925 chervonets is considered a trial one. Gradually, its production was abandoned.

Gold remake chervonets began to be produced in the second half of the twentieth century (1975 - 1982). Moreover, even after the collapse of the USSR, they served as a means of payment for some time. This continued until 1999, and in 2001 the use of "sowers" resumed.

Dutch Russian ducats

Under Anna Ioannovna, a secret semi-legal minting of chervonets, identical to Dutch ducats, was founded in Russia. The production of these coins, nicknamed "lobanchiki" or "arapchiki", continued until the official protest of the Netherlands in 1869.

The economy of the Russian Empire required easily recognizable coins that would inspire confidence abroad. Ducats, whose appearance had not changed for many centuries, were perfect for this role. The manufactured counterfeits played a major role in Russia's international trade and facilitated the supply of military campaigns outside the country.

Regular and double: golden chervonets of Peter's daughter

During the reign of Elizabeth, ordinary chervonets were mostly minted, but in 1749 double circulations were issued. Under the empress, other large denomination gold coins appeared:

- 2 rubles;

- 5 rubles (“half-imperial”);

- 10 rubles (“imperial”).

The imperial and semi-imperial were intended for use within the country, and the chervonets (regular and double) were for foreign trade.

It is worth noting that the image of the Apostle Andrew briefly returned to the chervonets in 1749 (in addition to the regular and double chervonets, the same “Andreev’s” ones were minted in these years).

Price

The cost of a 10 ruble gold coin from 1901 largely depends on a number of factors. Some have a slight effect, others can significantly reduce or increase the price tag:

- Instance state. This factor is given primary attention. For example, a poorly preserved specimen (G) will be much cheaper than a chervonets in excellent condition (MS);

- Place of purchase. The cost at auction or from the hands of an intermediary are often completely different things. If at auction the price depends on demand, then the intermediary strives to earn as much as possible from the service;

- Delivery method, terms of purchase. These details are discussed individually by the parties to the transaction, based on the results of which the final price is determined;

- Time to buy. The price of coins increases over the years, and if it is also spurred by active demand, then the cost can increase significantly. The quotation of precious metals also plays an important role.

Below is a table of the average cost of the coin “10 rubles 1901 AR or FZ” at auctions.

| Coin | Price in rubles |

| Federal Law | 40000 |

| AR | 80000 |

| Soviet coinage | 80000 |

A study of auctions shows that the starting price can sometimes start at 1000 rubles, but the bids for the lot end up being at the level of the average price from the table. We should not forget that value is a conditional thing, therefore the final price for a coin is set directly by the seller and buyer, with mandatory confirmation of the authenticity of the sample if the transaction takes place outside of the auction.

Chervontsi on the eve of the revolution

After Paul I, only counterfeit Dutch ducats continued to be issued in Russia from coins that were called “chervonets” and had no denomination.

Under Nicholas I, to reduce platinum reserves in the treasury, platinum chervonets were minted for some time. Gold coins began to play an important role in the country’s domestic market only towards the end of the 19th century.

Fifteen turned into ten

During the 19th century. The Russian economy failed to overcome the discrepancy in the value of paper and metal money. By the end of the century it was necessary to reform the monetary system.

After the reform of Minister S.Yu. Witte's main monetary unit could have been bimetallic coins. However, their stability was questioned, and the new specimens, released in 1895-97, were made of 900 gold.

The new coins received the old name - imperial and semi-imperial, but their denomination was increased to 15 and 7.5 rubles. The Nicholas Imperial corresponded to the ten-ruble imperial of Alexander III. On the obverse of the chervonets there was a portrait of the sovereign.

The circulations were large (sometimes issues were even ordered abroad), so the value of many Nikolaev chervonets is now estimated only by the precious metal content in them.

The last issue of chervonets under Nicholas II dates back to 1911. However, a century later, there are hundreds of times more coins from this year of issue than indicated in official documents. Probably, during the revolution and after it, chervonets were minted underground.

Coin Rus

Trial copies of the new monetary unit “Rus” were issued in 1895. The denomination of the coin was ⅓, ⅔ and one imperial. However, the new name was never used, and proof copies are now owned by museums and private collections.

Russian 100 francs

The collector's coin was issued in 1902 (900 gold, mintage 235-236 copies). On its reverse there are both Russian (37.50 rubles) and French (100 francs) denominations. Perhaps this circulation was going to be used to strengthen diplomatic relations with France. All copies released in 1902 were presented to the Tsar's relatives.

Coronation Jubilee 1906

Chervonets of Nicholas II, issued in an edition of 10 copies in 1906, is one of the most expensive Russian coins. This was probably a test mint in preparation for the coronation anniversary.

The cost of coins depends on their authenticity, age, condition, size and characteristics of the circulation, and the number of surviving copies. “Royal Metal” lives up to its name: some chervonets are so rare that they can only be seen in a museum. Such coins stand out from the rest due to their quality and release features and, despite their high cost, attract the attention of most collectors.

Nikolaev chervonets

The reign of the last monarch of the Russian Empire, Nicholas II, presented domestic numismatists with a wide variety of coins, among which gold specimens called chervonets are especially notable. This term is considered obsolete, but in colloquial speech it is often used to refer to ten-ruble bills. Initially, this word was used as a definition of gold coins, since in Rus' copper was added to the ligature for the production of such copies; it gave the noble metal a red tint, which is where the name red gold, that is, red, came from. Nikolaev chervonets were minted in multi-million circulations with many varieties of portrait types on the obverse. Currently, some of this money is used as investment material, while collections are collected according to absolutely different criteria, including the so-called “Soviet” and “tsarist” coinage. Let's consider this topic in more detail.

Witte's monetary reform

In the winter of 1895, Sergei Yulievich Witte presented a report to Nicholas II on the need to introduce a gold standard to strengthen the national currency, which would soon contribute to the economic recovery of the state. In domestic circulation, full-fledged gold and silver coins did not exist since 1885; the main currency for the population was banknotes, which, although backed by precious metals, were not exchanged by state and private banks for a hard equivalent. Because of this, such means of payment did not inspire confidence among citizens. Gold chervonets, previously used only for interstate payments, would strengthen the authority of the ruble.

Banknote 25 rubles sample 1892

Thanks to long and meticulous work, the first trial batches of imperials and russ appeared at the St. Petersburg Mint. A feature of these options was a double denomination, but they were not approved. The Nicholas Imperial was produced for three years in a row in batches of 125 pieces, which is why its cost is currently over a million rubles. The Rus produced only a few sets, so now they can only be seen in state museums.

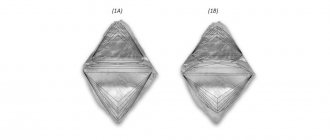

Obverse and reverse of double denomination gold coins

As a result of transformations in 1897, coins appeared in denominations of 5 rubles, 7 rubles 50 kopecks and 15 rubles. The 900 standard and the metal content in them corresponded to the coins from the reign of Alexander the Third, but their denomination was changed by one and a half times. It turned out that the old 10 rubles were equal to 15 new ones. The following year, a 10-ruble coin also came into circulation.

Reverse of gold coins from the reign of Alexander III and Nicholas II

The reform carried out significantly improved the economic climate within the state and made it possible to increase Russia's potential in the international arena. This allowed domestic businesses to attract Western investment.

5 rubles

The smallest and at the same time the most widespread Nikolaev gold coin turned out to be 5 rubles. Their minting began in 1897 and continued until 1911. During this time, the total circulation was approximately 130 million copies. Despite this, some specimens still remain relatively rare and cost several hundred thousand rubles. According to the technical characteristics, the weight of each was 4.3 grams (pure gold - 3.87 grams), diameter - 18.5 mm, and thickness - 1.2 mm. On the obverse along the edge there is an inscription: “B.M. NICHOLAS II EMPEROR AND AUTOCRET OF ALL RUSSIA,” and in the center they presented the profile of the emperor. The reverse depicts the Small State Emblem of the Russian Empire, model 1883, below it the denomination and year of issue are indicated. A pattern was depicted on the edge, interrupted on one side by two letters denoting the initials of the mintzmeister, and on the other by a rhombus.

5 rubles 1898

There are six main types of portraits of Nicholas II. The most valuable red nickels are considered to be those issued after 1904, since their circulations relative to previous issues were small (1910 - 200,018 copies, 1911 - 100,011 copies) or were minted in single copies (1906 - 10 coins, 1907 – 109 coins, the number of 5 rubles of 1909 has not been established).

7 rubles 50 kopecks and 15 rubles

The design of the obverse and reverse of 7 rubles 50 kopecks and 15 rubles coincides with the previously described denomination, however, instead of a pattern, the inscription on their edge was written: “Pure gold 1 spool 34.68 shares A●G” and “Pure gold 2 spools 69.36 shares A ●G.” The indicated letters “AG” are the initials of Apollo Ludwigovich Grashof, who served as manager of gold and silver coin redistribution at the St. Petersburg Mint from 1883 to 1899.

7 rubles 50 kopecks and 15 rubles 1897

These coins can only be found with a single date – “1897”. According to V.V. Uzdenikov this year, 11,900,033 pieces of 15-ruble notes and 16,829,000 coins of 7 rubles 50 kopecks were minted, after which the minting was stopped. According to the technical characteristics, the imperial (15 rubles) weighs 12.9 grams (of which 11.61 grams are pure gold), the diameter is 24.6 mm, and the thickness is 1.9 mm. The weight of the semi-imperial is 6.45 grams (of which 5.8 grams are pure gold) with a diameter of 21.3 mm and a thickness of 1.2 mm. Since they were not produced for long, at the very beginning of the reign of Nicholas II, excellently preserved specimens are very rare and valuable.

10 rubles

The last coin is often called the Nicholas Chervonets. The gold ten-ruble note is the most attractive collectible and investment material from the coins of the imperial period. She earned this position thanks to her large circulation. The pure gold content in it is approximately ¼ ounce, which is convenient for calculations. It is also famous for its considerable variety of obverses, combined with various initials of mintzmeisters, and several varieties of reverses.

10 rubles 1899

The design of the chervonets does not stand out, the inscription on its edge says: “Pure gold 1 spool 78.24 shares,” followed by the initials of the master of the mint. The weight of the coin is 8.6 grams (of which 7.74 grams are pure gold), diameter – 22.5 mm, thickness – 1.7 mm. However, it is on it, and not on the more widespread 5 rubles, that the largest variety of portraits is distinguished. When combined with other sides of the coin, the full collection of varieties amounts to several hundred pieces. And the most widespread year of minting of chervonets - 1899, provides the largest selection, for example, a “special” type of portrait of Nicholas II, found exclusively with a date of 1899 and the initials “FZ” (Felix Zaleman).

Soviet coinage

The most controversial topic regarding gold chervonets remains the Soviet coinage. The very issue of tsar-style coins at the Leningrad courtyard in the period from 1923 to 1926 causes quite logical bewilderment. However, thanks to the archival work of a number of historians and numismatists, it was possible to understand this complex issue and establish this fact. However, the quantity of such money, their dates and denominations are not reliably known.

A young state with a weakened economy due to ongoing international conflicts and civil war needed a reliable currency. The production of large silver coins according to pre-revolutionary standards, but with a new design that appeared in 1921, did not ensure the circulation of the necessary money supply. Because of this, they began to accept the royal gold coin for payments. It is also worth noting that they refused to sell imported goods for Soviet Russia for Soviet money, and the reserves of the old red coin were running out by that time; all these circumstances forced the production of such copies to begin in 1923. In parallel with this, work was organized on the design of a new currency and in the same year a coin with a denomination of one chervonets was minted, later called the “sower” among numismatists; its technical characteristics and gold content corresponded to the imperial 10 rubles.

Chervonets 1923

Experienced numismatists distinguish coins of the “Soviet” mintage from the “tsarist” ones, highlighting in them the mistakes made by the craftsmen of the Leningrad court when issuing chervonets. For example, the “late” type of portrait, characteristic of coins since 1900, suddenly appeared on ten-ruble copies dated 1898 and 1899, and on 5 rubles of 1897 and 1898 two types of “big head” portraits, which were made in later times, are widely found. years.

Gold coins of Nicholas II, presumably from the Soviet period of minting

The initials of the mintzmeisters were also changed. For example, the letter “G” with an elongated ending resembles a gallows, and the letter “P” is depicted in the form of a flag.

Edge inscriptions of gold coins with various types of writing of the initials of mintzmeisters

However, such signs are indirect, and indeed frequent experiments in production could have caused the appearance of uncharacteristic specimens even under the monarchy. Therefore, in collection catalogs you can often find the postscript “probably Soviet coinage.” But there is an exception. The 1911 Nicholas Chervonets, according to the reporting documents of the St. Petersburg Mint, was produced in a modest edition of 50,011 pieces. This circumstance should have made the specimens very rare, but they are common. Most likely, the instrument from the last year of minting was preserved in good condition, which made it possible to launch the production of many thousands of copies dating back to 1911. It is extremely difficult to identify “Tsarist” and “Soviet” coinage, but there are indirect signs. It is assumed that the alloy for the Nikolaev chervonets in the 20s was prepared in a different ratio of metals. The gold content of the supposed later coins is slightly higher, the copper content is lower, and silver is either absent or present in percentages. However, the vast majority of coins with the date 1911 are Soviet.

Work on studying the archives and the chervonets themselves continues, so new interesting facts may soon appear.